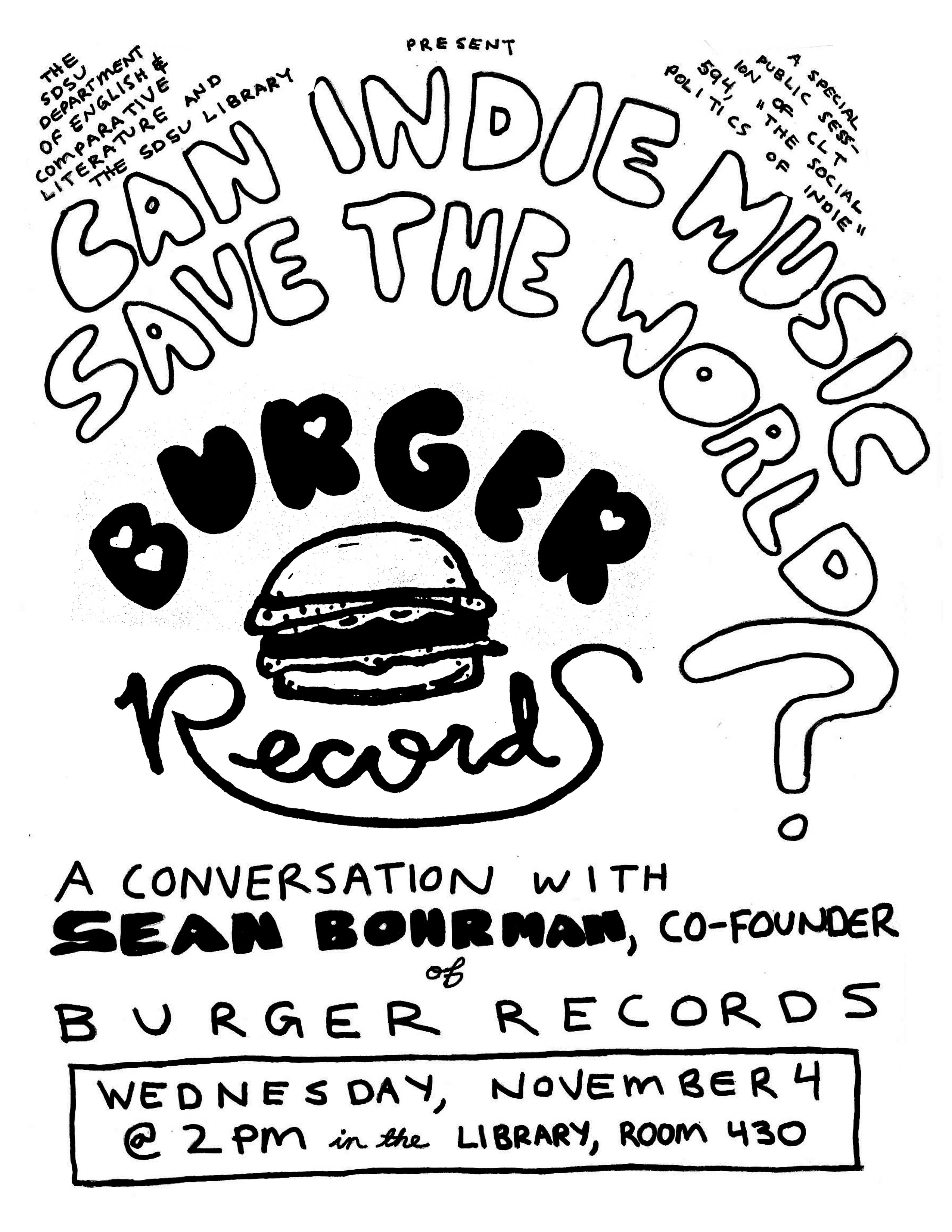

In November 2015, I invited Sean Bohrman — co-founder of Burger Records — to talk to my SDSU undergraduate class, “The Social Politics of Indie.” He very graciously accepted, I made a poster, and students came out in droves. It was the best-attended event I’ve been to at SDSU (granted, I’ve only been here for a few months) — and the reaction to the talk itself was borderline ecstatic. A bunch of my students said that Sean inspired them to start their own labels, or make their own music, or start a zine, or just to embrace the DIY spirit generally.

My intro script and my questions are pasted in below. For the most part, Sean didn’t take the ideological bait — he didn’t want to create hard oppositions of mainstream/underground culture, and he didn’t want to frame Burger in the tradition of politically-inflected indie labels like Dischord or Sub Pop or even K. My students mostly thought that was great — they’re totally resistant to the mainstream/underground opposition that meant so much to me in my teens and twenties and still to some extent today — though one student asked a great pointed question at the end: what motivates you to expand if you don’t have a social mission?

Huge thanks to Sean for coming to SDSU! And equally huge thanks to English & Comp Lit and the Library for supporting it and ITS for filming it. I hope these kinds of events become a tradition at State.

Intro Script

Thanks for coming to this special session of the SDSU undergraduate class CLT 594, “The Social Politics of Indie” — a course where we look at the connections between DIY movements in literature, music, and videogames. Today’s session, sponsored by the SDSU Department of English and Comparative Literature and the SDSU library, is called “Can Indie Music Save the World?” and our guest is Sean Bohrman, co-founder of Burger Records.

Our class starts from a simple question: what is the relationship between independent production and progressive politics in the arts? Did experimental modernist writing by people like Virginia Woolf and James Joyce happen in the early twentieth century because of the advances in printing technology that made small press publications and self-publishing possible? Would Riot Grrrl have made its massive contribution to third wave feminism in the early 1990s without the development of photocopiers for making cheap zines and cassettes for DIY music distribution? With the arrival of independent videogame production and distribution, should we expect a new form of socially progressive games that push beyond the white-male-dominated producers and audiences that fueled the ugly Gamergate controversy?

I’ve been obsessed with indie music since I was a teen. I grew up in London, Ontario, Canada, but my imagination was mostly in indie meccas far away in place and time — the real London, for example, or other mythical places with appropriately Greek names like Olympia, Washington or Athens, Georgia. I got a chance to be part of a vibrant, if somewhat less mythical, indie scene in my twenties when I lived in Toronto. When I found out I’d be moving to Southern California, I was excited about the weather and the surfing and the year-round cycling, but racked my brains a bit when it came to music. I associated SoCal with angry, hyper-masculine hardcore bands — not really my thing. When I arrived in San Diego and at SDSU, I felt a bit out of my element — until I stepped into this course, and met my students, who make up an amazing slice of the local indie culture. Things got even better when one of my students, Angela Risi, suggested I should check out Burger-A-Go-Go, an all-female music festival in Santa Ana headlined by heroes of the 90s underground like Kathleen Hanna, Kim Gordon, and Chan Marshall and featuring heroes of the today underground like Cherry Glazerr, the Aquadolls, and Peach Kelli Pop.

As an East Coaster, going to that festival was one of the weirdest things I’ve ever experience. In Toronto, I walked or rode my bike to see shows, always in one of about 5 clubs all in roughly the same, clearly-identified and tightly-delimited hipster neighbourhood. Here, I drove through the Southern California maze of highways to an industrial park in an anonymous part of Orange County. I paid $10 to park my car in front of a biotech firm and walked to the venue, wedged between a Home Depot and a hospital. Once inside, though — boom — here was the scene! Young badass people being themselves and making art and being creative. It’s once thing to build a scene in a place that was designed to support one. It’s another to build one, against all odds, in an industrial park. That is the legendary achievement of Burger Records, of which Sean Bohrman, our guest, is the co-founder.

Questions:

CHILDHOOD

How important was music to you growing up? How much a party of your identity?

How important was “indie” or DIY as a concept to you growing up?

What was the Orange County scene like back then?

Were zines a big part of the scene?

UNIVERSITY AND DECISION TO START A LABEL

You’re now at the southernmost CSU campus. You studied at the northernmost CSU in Humboldt State. Why Humboldt? Why journalism? Did anything about your college experience influence you to start a label?

What sorts of jobs were you working after college?

How does a person start a successful label? Like, at a practical level?

Bands like Beat Happening and labels like K Records have put a lot of importance into tapes. The first K Records newsletter features a cartoon illustration of a heroic K shield defeating a many-armed vinyl-spewing “corporate ogre” using only a cassette tape. Why did you start with tapes?

Is there a Burger “sound”? How do you pick which bands to put out?

In an era when it’s so easy to record and release music using tools like Garageband and sites like Soundcloud and Bandcamp, how has the role of labels changed? What do labels “do”?

POLITICS OF “INDIE”

A lot of the archetypal label bosses have tended to picture themselves as having an important social mission:

In one of his early Sub/Pop zines, Bruce Pavitt wrote,

Only by supporting new ideas by local artists, bands, and record labels can the US expect any kind of dynamic social/cultural change in the 1980s. This is because the mass homogenization of our culture is due to the claustrophobic centralization of our culture.

Burger is usually seen as a kind of good-times party label. But does this sense of political mission resonate with you?

Bret Lunsford of Beat Happening said that what was special about Olympia in the 80s and 90s was the existence of an “infrastructure” — “between fanzine to weekly entertainment magazine to radio show to label to club” — that, as he said it, then allowed “things to start happening.” What does the infrastructure look like in Orange County?

The Riot Grrrl political movement grew out of the indie music scene in Olympia and DC. Burger-A-Go-Go is the closest thing to a modern-day Riot Grrrl festival. Why this focus on female bands?

RELATIONSHIP TO MAJOR LABELS AND THE MAINSTREAM

One hallmark of indie culture is definition yourself against the mainstream. But in recent years that distinction seems to have broken down. Pitchfork reviewing top-40 music. Grimes manags by Jay-Z’s team. Carrie Brownstein on Portlandia. Miranda July falling in love with Rihanna. How does the notion of the “mainstream” fit into Burger’s self-definition?

Carrie Brownstein’s bio: lots of stuff about the suffocating insularity of the indie scene. The rules against selling out; the us vs. them mentality. Are there rules like that in the Orange County scene?

What’s your position on bands going to larger labels? Some legendary indie labels have found hard to keep their most valuable bands — Joy Division and New Order on Factory, The Smiths on Rough Trade — where other small labels have encouraged bands to move on: the Human League on Fast Product, Orange Juice on Postcard. How does Burger fit in?

BIG PICTURE

What are the Burger releases you’re proudest of?

What music are you listening to right now?

What’s next for Burger?