Count me among those pleased Dylan won the Nobel Prize today. Only snobbery can explain so many writers’ outrage at his win. If you think that Dylan isn’t a “real poet” because he likes to sing his poetry out loud and set it to music, you’re denying the history of poetry as an oral form often set to music. Perhaps you’d object to Homer being given a Nobel.

But it’s an instructive form of snobbery. It’s interesting how many people are loudly proclaiming that music lyrics, that pop lyrics, rap lyrics, aren’t poetry. It can be very useful to have such a concrete demonstration of such a flawed assumption on such a grand scale. It gives us all a chance to ask them the question, “Why isn’t Dylan a poet? What definition of poetry can you come up that can exclude his work?” My guess is that all they’ll be able to come up with is that it’s set to music (obviously wrong, viz. Homer) and that it is a “low” form enjoyed by too many people (obviously wrong, viz. Homer).

Here’s another little tiny concrete example of why Dylan is obviously a poet.

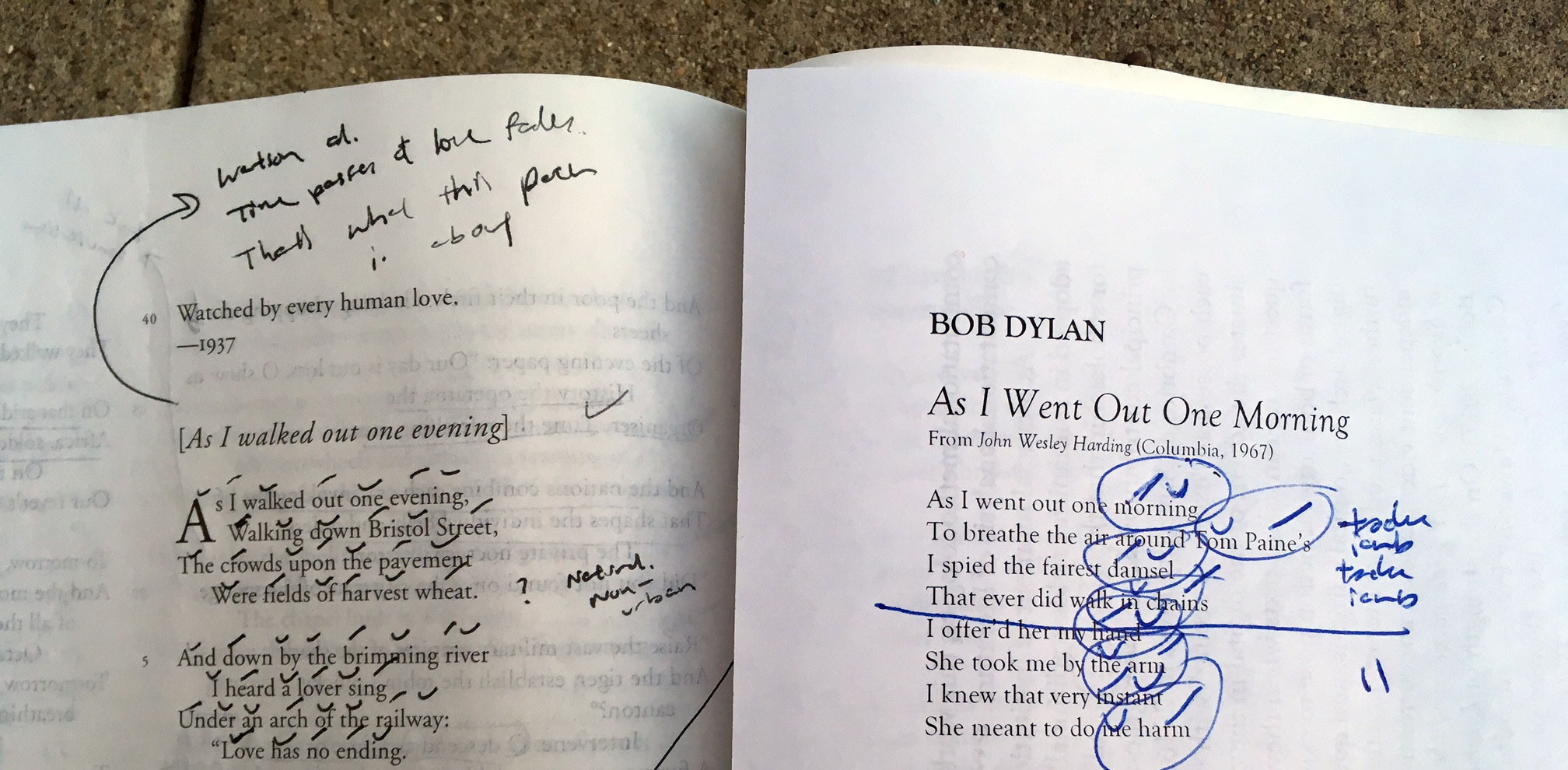

This is based on an exercise I did in my British Modernism class last semester. I was looking for a way of teaching prosody that wouldn’t seem totally boring. So I paired some Yeats poems (super interesting prosody!) with some Kenrick Lamar songs (super interesting prosody!). And I paired Auden’s “As I Walked Out One Evening” (1938) with Dylan’s “As I Went Out One Morning” (1967).

The question for the lecture was very simple: Is it a coincidence that these two works have such similar titles, or is there a direct influence? Is Dylan responding to Auden — and, if so, how do we know?

The first move was to establish that Dylan read poetry — and, more specifically, modernist poetry. I imagine that a lot of today’s outraged writers assume that any pop musician is probably too uncultured to read poetry (especially modernist poetry). That just gives away how uncultured these outraged writers are. Of course Dylan read poetry. He was obsessed with Verlaine and Rimbaud, as we know from his autobiography — and as we know, duh, from the lyric in “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go,” “Situations have ended sad / Relationships have all been bad / Mine’ve been like Verlaine’s and Rimbaud.” Which is a pretty brilliant lyric. And of course he has Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot “Fighting in the captain’s tower” in “Desolation Row.”

And then there’s his name. He was born Robert Zimmerman. He called himself Bob Dylan. Dylan, like Dylan Thomas. He took his name from a modernist poet. His name!

So, hmm, Dylan read poetry. Probably much more than his detractors have read. And poetry was so important to him that he named himself after a poet.

So it is not absurd to assume that he has read Auden’s “As I Walked Out One Evening,” and that “As I Went Out One Morning” is in some way a response to it.

In terms of content, the two are fairly similar. Auden’s poem is — like almost all his love poems — about the fantasy of romantic love. As Auden’s speaker walks out one evening, he hears a lover singing about how his love will never die. Then the city’s clocks offer their response, saying that love fades, that time always wins out. In one of the lovelier and more depressing stanzas, Time sings,

‘The glacier knocks in the cupboard,

The desert sighs in the bed,

And the crack in the tea-cup opens

A lane to the land of the dead.

Dylan’s song is also about love, but it’s message isn’t as clear. As the speaker walks out one morning, he sees a beautiful woman, but she’s a little too eager in accepting his advances. (Poets, try expressing that situation any better than this: “I offered her my hand / She took me by the arm.”) She’s desperate to leave with him, he doesn’t want to go, and then a man (Tom Paine) comes to take the woman away with him, apologizing for her indiscretions. (This tale of the vicissitudes of romantic love has been read as a parable about the left wing’s too-tight embrace of Dylan as a political prophet. This reading depends on making the connection to Dylan’s very odd acceptance of the Tom Paine Award.)

Content-wise, the similarities are tempting. But you’re not going to prove a connection that way. Thankfully, the form of the two works provides the required evidence.

Both works (for convenience, can we just call them poems?) are ballads. The anthology I assign to my students, The Broadview Anthology of British Literature, defines a ballad as “a folk song, or a poem originally recited to an audience, which tells a dramatic story based on legend and history.” Sensitive snobs will see that even a respectable anthology explains how the ballad form blurs the already slippery line between poem and song. Ballads are non-snob forms. They are traditional, popular poems with highly oral structures, meant to sound nice and to entertain, meant to tell a riveting story.

Although we think of Auden as a very “high” sort of poet today — no one complaining about Dylan’s Nobel would have complained about Auden getting it, though never did — he was very attached to these sorts of poems. He liked rhyme, he liked narrative, he liked poems that people wanted to recite out loud and get stuck in their heads. Why did he feel like this? Probably because of (certain members of) the previous generation’s obsession with rejecting the restrictive pleasures of oral verse — rhyme, regular rhythm, etc. How strongly did he feel about this? In 1937, one year before he published “As I Walked Out One Evening,” he edited The Oxford Book of Light Verse, a promotional vehicle for the sort of un-snobby, immediately compelling, nice-sounding poetry that writers like Eliot and Pound had made unfashionable. One of the poems in that anthology, notably, is “The Sailor’s Return,” the first lines of which are, “As I walked out one night, it being dark all over / The moon did show no light I could discover.”

So Auden’s poem is a ballad — and, moreover, it makes a very deliberate reference to an earlier, traditional ballad, a particularly choice example of the kind of “low” form he wanted to promote.

Dylan’s poem is also clearly a ballad. But is it a very deliberate reference to Auden’s poem?

Yes it is. Here’s how we know.

Not only are Auden’s and Dylan’s poems both ballads, they both also share a property of the “ballad stanza,” in that they’re both made up of four-line stanzas (quatrains) rhyming abcb. So there is that.

More curiously, they both share the same highly unusual metrical pattern. Neither is very consistent in the number of syllables or even stresses in a line, but they always follow the same strange pattern of end-line stress. Lines 1 and 3 of every stanza end with a trochee — a stressed followed by an unstressed syllable. Listen to Dylan sing “MORN-ing” and “DAM-sel” — those are trochees. But lines 2 and 4 of every stanza end with an iamb — the reverse pattern, an unstressed followed by a stressed syllable (“tom PAINE’S” and “in CHAINS”). So both poems have the following decidedly weird stanzaic structure with the same alternating pattern of end-line stress:

Yadda yadda TROCH-ee

Yadda yadda i-AMB

Yadda yadda TROCH-ee

Yadda yadda i-AMB

Maybe it’s a coincidence that Dylan came up with such a similar title to Auden’s. But there’s no way it’s a coincidence that he came up with a similar title AND made his poem a ballad AND and then gave it the same weird metrical pattern. This “alternating end-line stress” thing is really odd. It sounds strange when Dylan sings it, like he’s straining to squeeze the words into its awkward reversing pattern, especially in the line quoted above, “I offered her my HAAAAA-nd”. (There’s an advantage Dylan has over Auden: since its orality isn’t optional, you can always really, viscerally hear the weird metre.) There’s no way he’d come up with that if he hadn’t been reading Auden’s poem, noticed its strange alternating stress pattern, and decided to do his own version of it.

What is the significance of the pattern? I’m not sure. Maybe the alternating stress is an attempt to mirror the reversing vicissitudes of romantic love, the “forever/for now” of Auden’s lover, the Dylan’s speaker’s attraction/repulsion to the distressed damsel.

On some level, though, poets want to leave those sorts of questions to us. They don’t need to know what it means to use a form like the “alternating stress” pattern. They just need to like it as an element of craft, a fun technical challenge to take on and give a shot at.

Or they just use it as a sign of respect — a shoutout to someone who meant something to them. That alternating stress pattern is a way for one poet to link his work to another’s.

It’s a high five, through 29 years of literary history, from one poet deserving of a Nobel prize to another.

Update: Since posting this a few hours ago, an editorial has appeared in the New York Times under the title “Why Bob Dylan Shouldn’t Have Gotten a Nobel.” Anna North, the author, writes, “Yes, it is possible to analyze his lyrics as poetry. But Mr. Dylan’s writing is inseparable from his music.” As I hope I have shown above, all poetry is “inseparable from its music.” Even a poem by a “real writer” like Auden depends on its music (its patterns of sound) to work its magic. That’s how poetry works. That’s what poetry is.