Since I got interested in running marathons a few years ago, I’ve wanted to run Boston. I think it’s mainly because of their ingenious marketing campaign, the concept of “BQ” (Boston Qualifying) times, which serve as shorthand in all age/sex categories as the standard of being a “good runner.” When I heard about BQ times, I wanted to BQ. When I BQed, I figured I should use my BQ to, you know, run Boston.

Yesterday, I did.

Boy, did I ever run Boston.

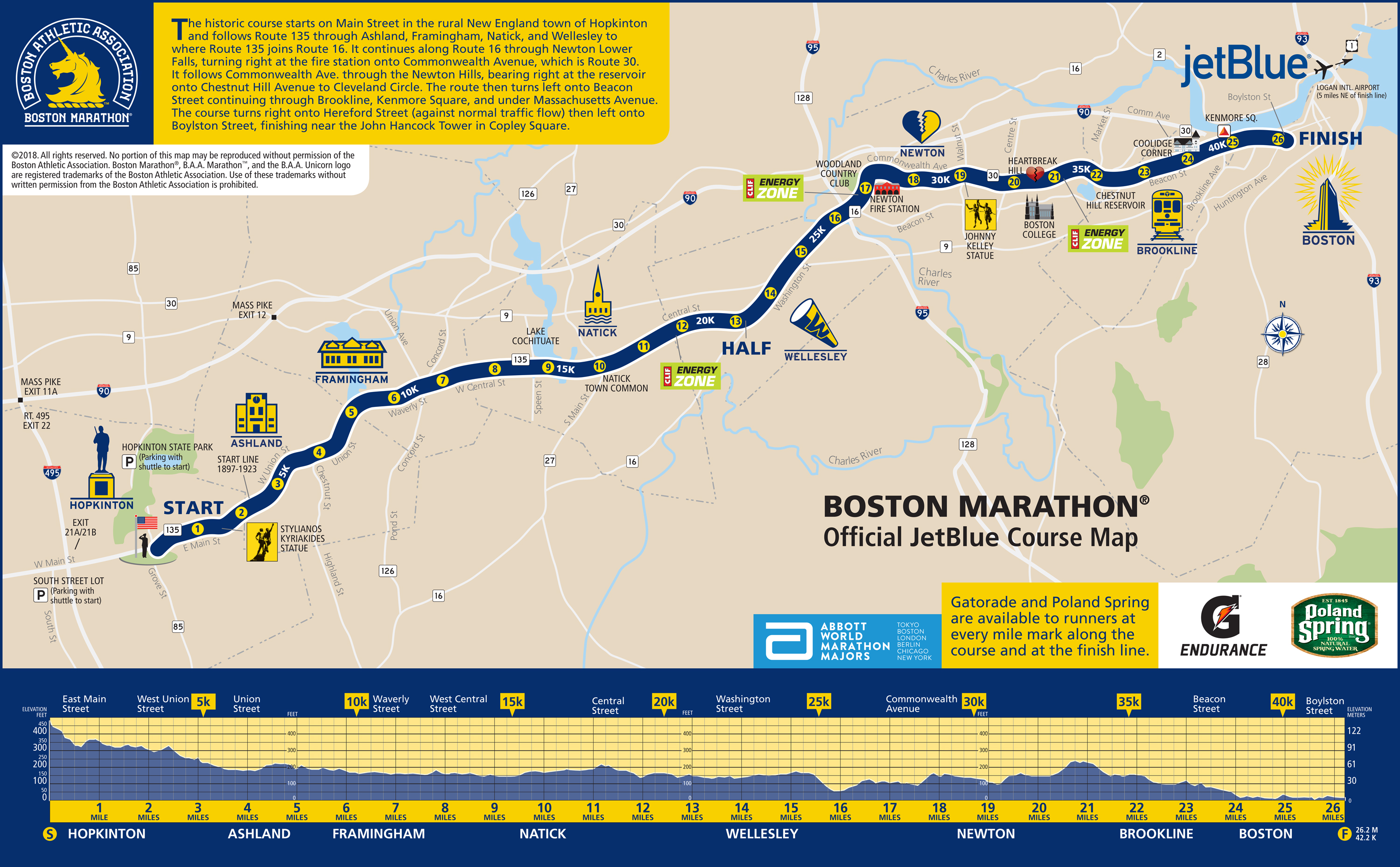

A big part of the appeal of Boston are things that are the same every year: the famous point-to-point course through picturesque small towns, the infamous Newtown Hills that break hearts and legs between miles 16 and 21, the rich history of the oldest continuously-run marathon in existence.

Another part of the mystique of Boston is something notoriously changeable: the New England springtime weather. Sometimes it’s insanely hot, sometimes it snows. Sometimes there’s an amazing tailwind, sometimes there’s a murderous headwind, and it’s with you the whole way, because the course runs pretty much straight east (and a little north).

Yesterday, I got the small towns, the heartbreaking hills, and the history. And I got the weather: it rained hard all day, it was barely above freezing, and there was a strong direct headwind the entire length of the course.

The conditions were not just awful, they were historically awful.

Meb Keflezighi, 42, winner of the 2014 Boston Marathon, called them “the toughest conditions I’ve ever run in.” Shalane Flanagan, 36, Boston native and winner of the 2017 New York City Marathon, said they were “the most brutal and gnarliest conditions I’ve ever competed in.” In The New York Times, Matthew Futterman called the race “epic — as in epic misery.” Placing 2018 in the history of notoriously miserable Boston Marathons, Futterman said “Monday was as high on the misery index as anyone I talked to could remember.”

Beyond these anecdotal accounts, the best measure yesterday’s brutal conditions were the performances of the elite runners. Des Linden’s winning time of 2:39:54 was the slowest in forty years (Gayle Barron, 2:44:52, 1978). Men’s winner Yuki Kawauchi’s 2:15:54 was the slowest in forty-two (Jack Fultz, 2:20:19, 1976). Most tellingly, less than half of the elite runners who started the race finished it: 23 of 41 elite runners DNFed, including 13 of 16 African runners.

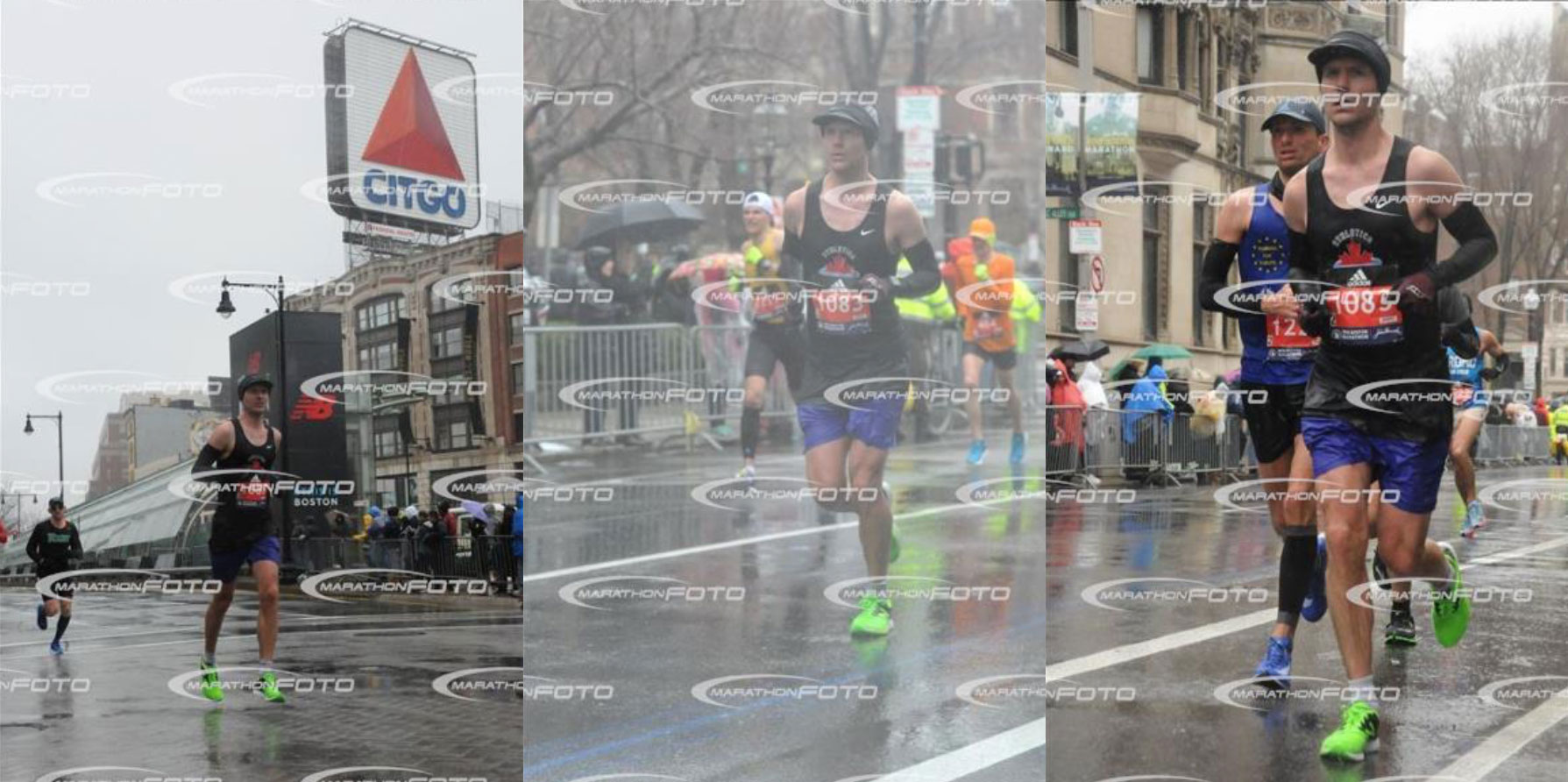

But I loved it. I loved the course, I loved the challenge of preparing for the awful weather (the forecasts were accurate ten days out, so I knew what was coming), and I had one of the most enjoyable runs of my life. I ran a very comfortable 2:52:40, never pushing myself and finishing with plenty left in the tank. My time was 5 minutes off my personal best of 2:47:19 that I ran in Los Angeles. But considering the mayhem of the day and how great I felt as I crossed the line, this was surely my best run to date.

The Backstory: Summer 5ks and the Toronto Waterfront Half

I haven’t written about running here in over a year, but I’ve been running. After LA, I took two weeks off and then decided to start training for 5ks. My body was in all sorts of pain after really pushing myself in LA, and I decided I needed a break from marathons. In April and May of last year — my last months in San Diego — I used a training program from Matt Fitzgerald’s 80/20 Running and really enjoyed all the short, fast workouts. When I got back home to Canada, I ran a 5k in Barrie, where my sister lives — and won it. A little while later, I ran another 5k in Toronto and came second. (In October, I came in first in a charity 5k, but I still feel a little embarrassed about that. It’s really not the kind of race you compete in. I got carried away.)

After these surprising triumphs, I shifted my attention to training for the Toronto Waterfront Half-Marthon in October. This time I followed the Hansons program, which is just a slightly scaled down version of their marathon plans, which I’d followed for LA and would follow again for Boston. The training was more monotonous and much longer, but absolutely fine. And I ended up having a great race day. Shooting for a sub-1:20:00 time, I shocked myself by finishing in 1:17:48 — by far my most competitive ever single run (still true after this Boston, I think). This was largely the result of slipping into a professionally-paced group of racers gunning for the women’s marathon title (the half-marathon course is essentially the first half of the marathon course, and the two groups start together). I just tucked in and held on. Since I didn’t have to think about strategy or even look at my watch, the time flew by, and the race was over in a flash. I crossed the line feeling great.

As much as I enjoyed all this shorter running, something was missing. I think it was pain, basically — and pain’s complement, good stories. Training was pretty easy, running the races was mostly pleasant, and I was always able to walk the next day. It was all pretty boring, it wasn’t worth writing about, I didn’t write about it. Sometime in the fall, I was notified of my acceptance to Boston 2018. I looked forward to the pain — and the stories.

Training for Boston

I made a serious tactical error after the Half in Toronto: I stopped running.

I thought it would be good for my body to have some time off — maybe a week. But then the weather immediately turned cold — around freezing — and I just didn’t feel like digging out my winter running gear. San Diego — where the coldest temperature I ever ran in was 7C, and where I never wore anything other than a singlet and shorts — had spoiled me. Also, I was very busy settling into my new job at U of T, teaching two courses I’d never taught before, and I’d just moved into a new house, which needed to be painted and furnished. I only ran a few times from the Toronto half to the end of November.

Then December came, and the cold was insane. With temperatures consistently around -20C (if you’re not from Toronto, this is insanely cold even for us), I had no desire whatsoever to get out and run. At some point around Christmas, I pulled out my Hansons Marathon Method book and realized I was already behind schedule; I was supposed to have started in mid-December. With work and the weather, I knew it would have to wait until January. I was at a conference in NYC at the start of January, and hoped to start things off with a few runs around Central Park. But: weather. There was an incomprehensible snowstorm that lasted the duration of my visit, with frigid highs of -20C and ridiculous winds. I could barely walk down the sidewalk, much less run.

It was becoming very clear to me that training for a spring marathon would be a totally different proposition in Toronto compared with San Diego. I thought I understood this going into it, but I really didn’t.

Finally, I got started around mid-January. But because I hadn’t run in almost two months, I needed to start slowly. I was hoping my body would thank me for the time off and be rearing to go, but that wasn’t the case, and I needed to ramp up my mileage slowly. When the time came for my first marathon-pace tempo run, I was hoping I’d be able to effortlessly pump out a 6:10/mile pace en route to my (for no good reason) ultimate goal of a 2:42 marathon. No such luck. I finished at 6:17/mile and wanted to die. (My average heart rate for that run was 166bpm, over 10bpm higher that my heart rate yesterday — though clearly the heart meter on my watch wasn’t working right in the cold.)

The rest of my training was pretty boring. I adjusted my goal to matching my LA pace of 6:24/mile, knowing that my missed 2.5 months of training and the brutal winter made a PR unlikely. I got hurt a few times, learned about all sorts of ligaments in my feet, watched a lot of Olympics balancing on one foot to strengthen my ankles, and eventually settled into a decent routine, hitting my mileage and pace targets.

The weather remained a problem, though. It was a really cold winter — and an even colder early spring. I figured I’d be able to test out my intended Boston apparel at least a few times during training. But from January to April 14, when I flew to Boston, we had only a handful of days with highs above 5C. Mostly, I ran in temperatures from -10C to 2C, which for me means long sleeves and pants. On a single day in late February, the temperature got up to 10C and I was able to run in shorts and a singlet. That was the only one. On a few days in April, I was able to run in shorts. All the rest — 95% of the time — I ran covered up from head to toe.

A 90F Boston would have absolutely killed me. As it turned out, I needn’t have worried. I trained in terrible, cold, nasty weather — which was ideal preparation for yesterday’s terrible, cold, nasty weather.

The week before Boston

As I mentioned, 10 days out the forecasts were calling for cold, rainy, windy conditions on Monday. Everything I read said not to worry — that even the best computer models couldn’t predict New England spring weather with that kind of accuracy that far out. But every model seemed to be predicting the same thing. So I decided to read everything I could about running in the cold, wind, and rain.

After many, many blog posts and magazine articles, I decided on the following:

- I would buy some Aquaphor, which Laura at the blog 50×25 swears by as a slightly preferable alternative to Vaseline for reducing friction and avoiding blisters. Knowing how much trouble I’ve had in the past with my feet and toes, this sounded like a good bet.

- I would buy a waterproof “skull cap” toque, which I’d wear under my hat and throw away if I got too hot. Since so much body heat escapes from the head (the image of George Constanza in his Russian sable hat is always with me), carefully planning my headgear seemed wise. I bought the cheapest MEC-brand skull cap.

- I would buy some arm warmers. Tight-fitting, thin clothes, easily layered, easily removable, seemed to be the best strategy for cold and rainy conditions. Rather than a bulky, flappy, difficult-to-remove long-sleeved jersey, thin arm warmers with a singlet seemed like the best plan. If it was going to be really cold or really wet, I’d smear Aquaphor on all exposed skin, which would keep it dry and warm. I bought the cheapest MEC-brand arm warmers. (By the way, I think one of the reason so many elites dropped out is that they didn’t dress properly. I hope you’re reading this post, elite coaches!)

It also became clear that I wouldn’t be able to run Boston in my preferred “fast” shoes. My Asics Hyper Tris have little holes in the soles, presumably to drain water from wet post-swim triathletes’ feet. In winter training, I noticed that water from wet roads would jump up through these holes and soak my socks. This seemed like a bad idea for Boston, so I decided to run with my normal-soled Fresh Foam Zantes, which are my main “slow” training shoe, but are quite light and very comfortable. (In practice, the Hyper Tris probably would have been okay; since it rained hard the whole time, and constant soak was inevitable, drainage was more important than sealing. But the Zantes were some comfortable that it seems like a non-issue.)

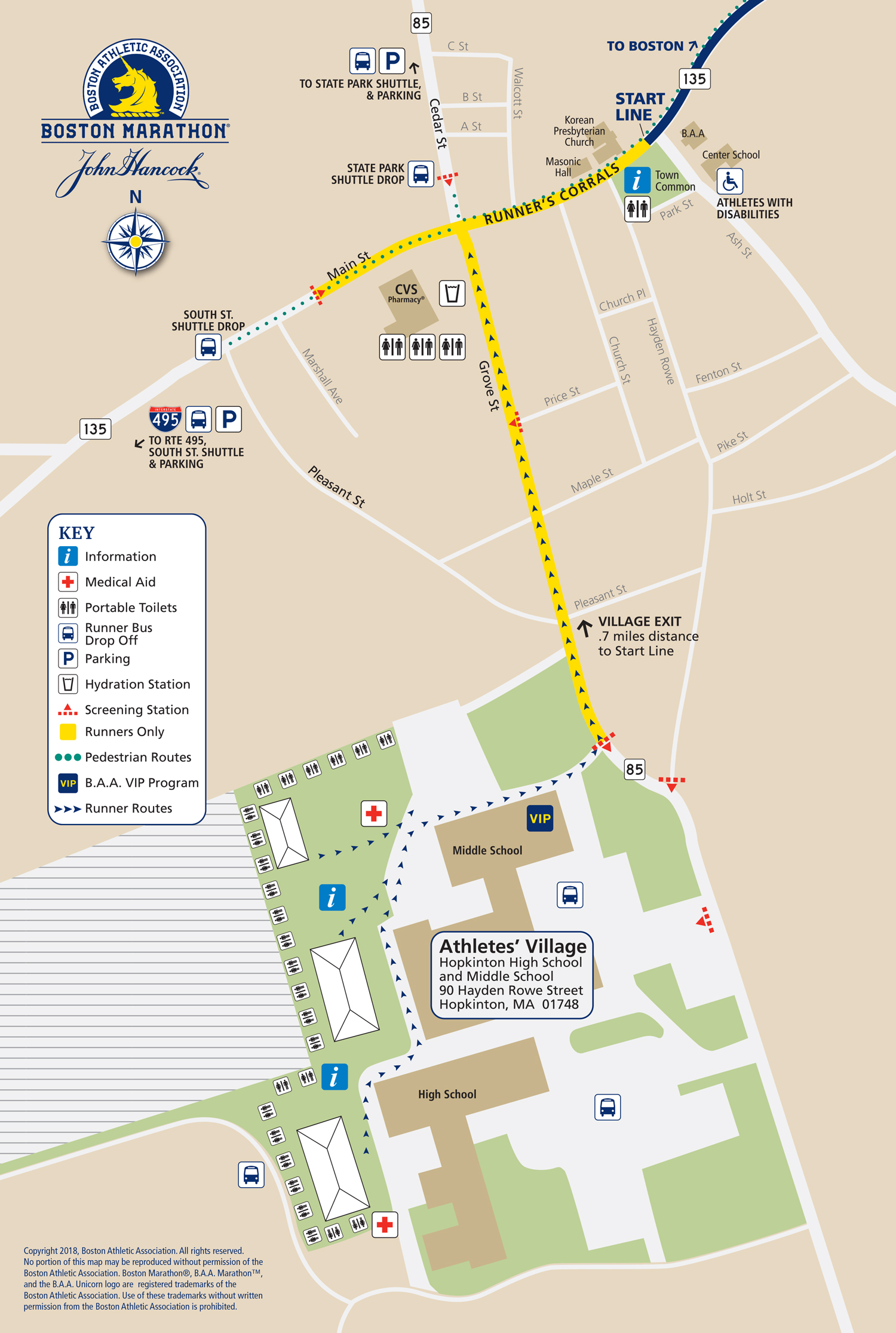

I also read as much as I could about the particular challenges of running Boston on a cold and rainy day. This has to do not so much with the course as with the strange ritual of how runners are shuttled out of downtown Boston to rural Hopkinton on race morning. (Boston is point-to-point: it starts 26.2 miles outside the city and heads back in). Although my race wouldn’t begin until 10am, I’d have to leave my Airbnb at 6am and spend most of that time outside, waiting for the bus to Hopkinton and sitting around in the dreaded “Athletes’ Village” for at least two hours before the race. Based on this, I decided on the following:

- I would buy a lot of warm, waterproof, layered clothing to wear the morning of the race. Since this would all have to be discarded (i.e., thrown away — though race organizers donate the clothing to charity), I would have to buy all this cheaply. I headed to my nearest Value Village and bought a pair of track pants, a fleece jacket, and an incredible waterproof shell with a hood (best $12.99 I ever spent). It wasn’t especially cheap — it came to around $35 — but it was well worth it, as you’ll see. That waterproof shell, especially, saved me.

- I would bring a pair of old shoes and some old, thick wool socks to wear to Hopkinton and discard them at the start line, changing into fresh socks and dry shoes right before the gun.

This research and preparation was the reason I had a good race.

Race weekend

The day I left for Boston, The Globe and Mail ran an article I wrote for the Travel section, “Why running a marathon is a terrible reason to travel.” In the article, I explained why the notion of marathon-tourism is so flawed. Basically, you can’t do any sightseeing beforehand because you need to rest, and you can’t do any sightseeing after because you can’t walk. I went in to Boston with that philosophy in mind: I’d arrive two days out, spend as little time at the expo as possible on Saturday, and rest and carbo-load on Sunday.

That’s pretty much how it went. It was a bit heartbreaking not to participate in all the fun marathon-themed things happening in the city, but I knew I needed to take it easy. I did allow myself to go to the Tracksmith shop on Newbury street to grab the gift bag they were handing out to marathon participants — and I took advantage of their free shuttle to the expo, which was at a conference centre really far away from everything else. Then I grabbed my bib and got back to my Airbnb near the Symphony subway.

Sunday, I lay in bed reading volume 2 of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels and stuffing myself with carbs: gummies (“Scandinavian Swimmers” from Trader Joe’s — yum!), pasta, coconut water, orange juice, bagels. I only left the house once. This was to walk to the local Goodwill and buy more clothes.

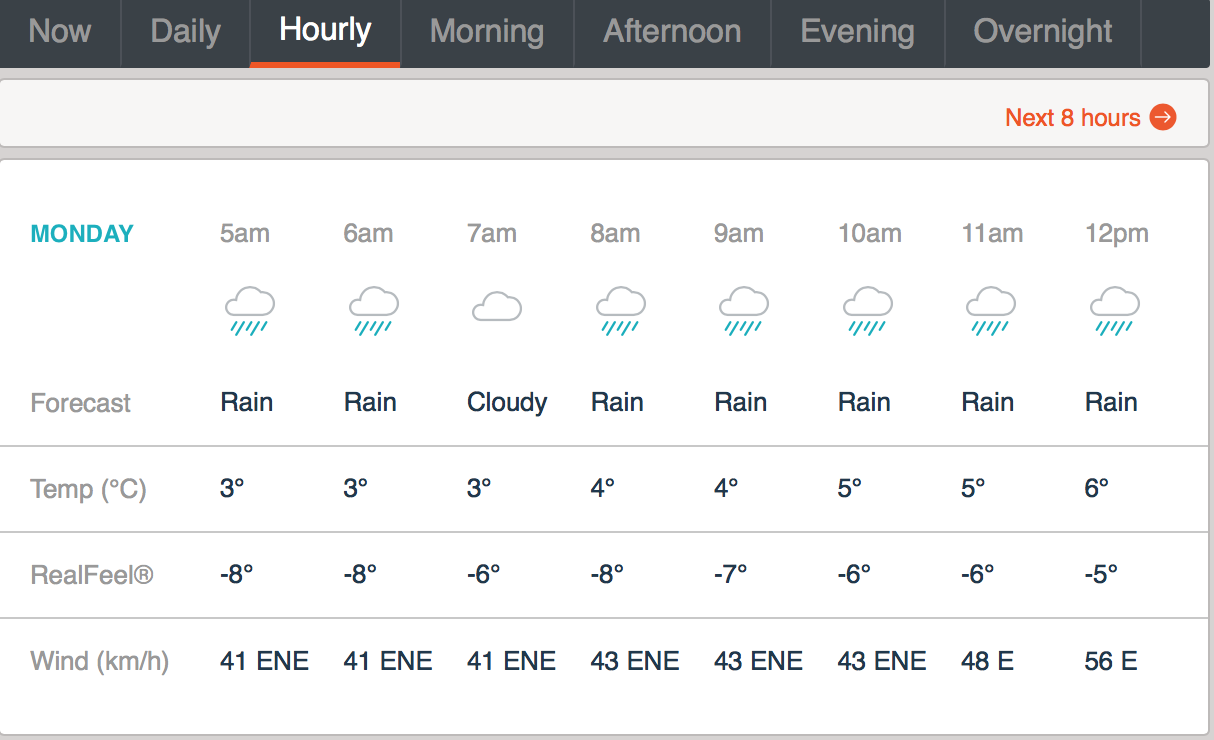

Like all Boston runners, I had been checking the weather reports obsessively for the previous 10 days. Those reports hadn’t changed much, but there were some variables, including exactly how much rain would fall (0.5-2 inches), how cold it would be (10-15C), and what the wind would be like (initially, a strong tailwind was predicted, then a moderate headwind). By Sunday afternoon, it was pretty clear that the weather was going to be worse in every way that the worst predictions: 2.5+ inches of rain, race-time highs of 7C, and a ridiculous 40-60 km/h direct headwind with gusts up to 80 km/h. Here’s a screenshot I took from Accuweather at 5:30am on Monday:

Goodwill was a 40-minute walk away, and normally I wouldn’t bother with that much exertion before race day. But I decided I needed another fleece, some heavy mittens, and an umbrella. I went, found what I needed, and spent another $10 or so. It was worth the expenditure of energy and cash.

The forecast also prompted me to rethink my race strategy. Clearly, with “feels like” temperatures well below freezing and ridiculous headwinds, it wouldn’t make any sense to stick to my goal pace of 6:24/mile. I did a bunch of reading to see how much a headwind of that velocity would affect me, but there was no firm consensus. The best advice was to “run to feel” rather than pace. Another thing was to draft as much as possible. I knew from my Toronto Half experience (and my years of cycling) how much of an effect drafting could have, and I knew it would be greater still with these ridiculous headwinds. But I’m tall, so drafting would only accomplish so much.

My overall takeaway was that I wouldn’t aim for any particular time. First and foremost, I’d just try to finish. I’d stay within myself and draft whenever possible. I’d dress as intelligently as possible. And I wouldn’t let myself get freaked out by what were certain to be horrific conditions. The best piece of advice I came across was, “The hardest thing about racing on a cold, rainy day is talking yourself into starting.”

Race morning

As always, I had a terrible time getting to sleep the night before the race. I had my earplugs, I took a Unisom, I didn’t try to go to sleep too early. But it still took me a couple of hours to fall asleep, and I’m sure I didn’t sleep more than 3 hours. I was up at 5:30, rubbing Body Glide and Aquaphor all over myself and getting dressed. While it’s fresh in my memory, here’s what I put on:

Head

- Layer 1: MEC skull cap

- Layer 2: Ciele hat

- Layer 3: Saucony headband, both to keep my ears warm and to anchor hat in place so it wouldn’t blow off in the wind.

I didn’t remove this setup once — not on the bus, not in the village, not in the race. It was perfect and I think was the most important part of my outfit. Remember George in that sable hat. I was never cold the entire day.

Upper body

- Layer 1: Nike Athletics Canada “Miler” singlet (a little more coverage than the Tracksmith BQ singlet I also packed — and black, which I figured might attract some warmth?), MEC arm warmers

- Layer 2: Thin fleece (Joe Fresh, Value Village)

- Layer 3: Thick fleece (Eddie Bauer, Goodwill)

- Layer 4: Waterproof, hooded shell (some obscure brand, Value village)

Everything but layer 1 was to abandoned in the village. This may sound like overkill, but one more thin base layer would have been even better.

Hands

- Layer 1: Ratty old thin Saucony gloves

- Layer 2: Salomon Thinsulate mid-weight gloves

- Layer 3: Wool mittens (Goodwill)

Lower body

- Layer 1: The same Nike shorts I’ve worn for every marathon (I was thinking of going with some newer Tracksmith shorts, but they don’t have pockets, and I wanted to be able to take things off and put them back on. If I had to do it all over again, spandex shorts would make the most sense.)

- Layer 2: Old New Balance lined pants (Value Village)

I definitely could have used another thin layer for the Athletes’ Village, but the shorts were perfect for the race.

Feet

- Layer 1: Adidas high-rise socks

- Layer 2: Thick wool socks

- Layer 3: Worn-out New Balance Zante shoes, probably from the LA Marathon training cycle

These were just for the village. For the race itself, I’d wear a single pair of Adidas socks.

Anyway. Dressed thus, umbrella in hand, with a bag containing my shoes, more socks, some gels, some food, and some caffeine pills, I left my Airbnb at 6:10. My first thought on stepping outside was that, despite the thermometer indicating 3C, it wasn’t that cold. This is what comes from training in a brutal Canadian winter, where 3C was well above average for me. It was already raining quite hard and was very windy. There were deep puddles all over the sidewalks.

I headed for the nearby Symphony subway station to catch a ride to Boston Common, where Wave 1 buses were loading between 6:15 and 6:45. The night before I’d bought a “Charlie Card” for the subway with enough credit for a single ride, knowing I wouldn’t have a credit card with me on race day, and thinking the three-stop subway ride was worth the trouble to avoid getting soaked on the 30 minute walk to the Common. Of course, when I got to Symphony, the machines wouldn’t read the card. So I got back out in the rain and jogged gently — so as to keep my temperature up without wasting too much energy — to Boston Common. By the time I got there, my feet were totally soaked, and I was absolutely covered in water, but my outfit was working: that blessed waterproof shell was keeping the water off me, and the old used New Balance pants were keeping my dry.

Already, in the lineup for buses, it was clear most people hadn’t read the same articles as me. There were a ridiculous number of people without any throw-away clothes, wearing only their thin race gear. They were already shivering in the cold and rain, waiting for their buses.

Luckily for me, I didn’t have to wait a single second for my bus: as I was passing by one, an organizer shouted, “room for one more,” and I snuck right in. The bus was a bog-standard yellow school bus. I got that awesome seat at the back where one half is occupied by the wheel well. I got it all to myself.

Bus Ride, Athletes’ Village, Corrals

A lot of people were chatting on the bus, but I just pulled my hood over my head and tried to conserve energy. My main objective on the ride was to eat my “breakfast”: two bagels and 500ml of beet juice, the same food I’d eaten before LA. I got this diet from Matt Fitzgerald’s New Rules of Marathon Nutrition, where he recommends eating 2-3 hours before the gun. I waited until 7am, 15 minutes after my bus left and exactly 3 hours to the gun, and started eating. It took me about half an hour to eat two bagels and drink the (disgusting, but very effective) beet juice — but there was time, as the bus ride took about an hour start to finish. (Non-runners: I know this is a very boring paragraph, but this is what the runners want to know!)

After staring out foggy school bus windows at unfocused globs of green, brown, and mostly grey, I arrived in Hopkinton at 7.45am, exactly 2 hours and 15 minutes before the race was to begin. My first stop was the “Athletes’ Village,” the schoolyard of Hopkinton Highschool, which for the day had been set up with two large tents (for runners to wait in) and one small tent (medical), and surrounded with a perimeter of what looked like a hundred porta-potties. I would be stuck here until 9:15, when the 7,700 Wave 1 runners would make the mile-long walk to the start corrals.

My first stop was one of the large tents, where people were just sitting around. By this point (with another 23,000 runners to pass through), the ground outside was already starting to get muddy, but inside it was mostly still grass. I found a relatively dry patch and sat on one of my bags. If I’d been really prepared, I would have brought a yoga mat and slept on it. I just sat there with my head tucked in to crossed legs, closing my eyes and trying to conserve heat and energy. I remained frozen in that pose for a full hour, one of the most boring of my life. When I occasionally looked up, the scene was not good. It was pouring outside, and the field was being mashed into thick, red-brown mud. People looked nervous; few were smiling or talking. Most of all, people looked cold. One guy had on what was probably his go-to marathoning uniform: a tiny singlet, short shorts, ankle socks, and racing flats. His shoes were totally soaked and completely covered in mud, he was drenched, and he was shivering violently, walking around the tent, getting muddier and muddier, trying to stay warm. There were still to hours to go to race time.

Apologies in advance for another paragraph that will only appeal to runners (even then, “appeal” isn’t the right word). At 8:45, with half an hour to go before the long walk to the corrals, I noticed that lineups were starting to form for the porta-potties. A hundred toilets may sound like a lot, but not for the 30,000 runners who would pass by that day, and not for the 10,000 who were probably already in that field. I got in line. My stomach had been rumbling since I drank my 500 disgusting millilitres of beet juice, so I had high hopes for a robust pre-race “voiding” (probably the single thing I get most stressed about on race morning). That went fabulously (sorry). I took advantage of the dry, private spot to apply some more Aquaphor to myself, all over my legs and anywhere I’d have exposed skin.

Back outside, I wandered around a bit, stepped in mud, and got a glass of water with which to take my caffeine pill (I’d been coffee-fasting for two weeks, which had been painful; the caffeine felt great). Wandering through the muck, I discovered some small red tents that the Clif Bar people had set up, which were heated. I pushed my way in there and spent a very pleasant 15 minutes warming up. Then it was 9:15 and time to walk to the corrals.

I knew I wouldn’t be able to get in a proper warmup with all the packed roads and terrible weather, so I did a light jog to the corrals. By the time I got there, got in line for another set of porta-potties, where I finally changed into my race shoes and socks, which had been in a sealed bag to this point. I milked my time in the porta-potty a bit (you know the weather is bad when you’ll do anything to stay inside a porta-potty), applying still more Aquaphor to my feet before putting on my fresh socks. (This clearly worked; incredibly, given the perma-wet state of my feet and my history of horrible blisters, my feet felt totally fine after the race.) By the time I got out, it was 9:45 or so. I popped my Tylenol, did some stretches and a bit of warming up, and walked to Corral 2.

I had read that if you’re in Corrals 1 and 2, you can see the elite men walk out of the Korean Presbyterian church where they warm up and walk to the starting line. I made sure to hang around the part of the corral nearest to the church. And then I saw them, two or three feet from where I stood, walking right past me to take their places. It was thrilling. I recognized Geoffrey Kirui, Galen Rupp, and Yuki Kawauchi, and I warmed myself up cheering for them.

Around me, a lot of people looked bad. Either they had taken off their warm clothes too early, or hadn’t brought any at all, but they looked freezing. A guy right next to me was shivering so badly that I could hear his teeth chattering.

I kept my clothes on until the last possible moment. At about 9:57, I removed them and stuffed them into a nearby “charity donation” bag, bidding a particularly bittersweet farewell to that waterproof $12.99 jacket. I swallowed a full gel, got my watch ready, and waited for the gun.

The race

Yes, I’ve already passed the 4,000-word mark on this post, and I’m only now getting to the race. I think that captures the experience of running any marathon, but especially this one. By the time the gun goes off, most of the important work is done. If you’re prepared, you’ll be fine. I felt prepared and I was ready to run.

For me, the first half hour of a marathon, before the suffering begins and all your thoughts become strategic, is the only actually enjoyable period. I spent the first several miles trying to take it all in. I looked around at the spectators, the scenery, the ridiculous weather. I repeatedly silently to myself, “You’re running the Boston Marathon.” The two things that impressed me most were how many people came out to cheer on a historically disgusting day — and how many good runners there were. In the first miles, it really struck me what a different marathon this was from Victoria and Los Angeles. In previous races, a few miles of running at my marathon pace would leave me in a thin pack of a few runners. By mile 5, the road was still absolute clogged with people running as fast as me and looking strong. (It wasn’t all ill-prepared, shivering people. 772 people finished faster than I did.)

I tried not to look at my watch too much and heed all the advice I’d read to go easy in the first miles. I mostly concentrated on staying tucked in behind tall runners going about my speed. The wind was strong, but I was surprised how well the drafting was working — it didn’t bother me nearly as much as wind bothers me when I out alone. The rain was heavy and cold — at times it felt like little balls of ice smacking the exposed skin — but once I’d warmed up a bit, it didn’t bother me very much. I was going about 10 seconds per mile slower than my goal pace, but it looked like a respectable time around 2:50-2:55 would be possible.

Nothing much sticks out from the first half of the race. I tried to push harder than other runners on the downhills and go easier on the uphills — a strategy that worked for me both in Victoria and LA. But mostly I tried to stay tucked in behind people going my pace, which meant I was constantly looking for new partners. In other marathons, I’ve found a group and stuck with them. In Boston, this didn’t happen.

I made my only important clothing decision around Mile 10, which was to take off my second layer of gloves — the Thinsulate Solomon ones. They were so waterlogged that I was constantly having to wring them out by making a fist. I began to wonder if all that extra water was weighing me down. I figured my thin Saucony gloves — Layer 1 — would protect me from the wind without all the extra weight. I removed the Solomons and tossed them to the side of the road. My first thought was that it was a mistake, because me hands immediately felt cold. But eventually my hands warmed up and were fine.

The moment that will stick out for me in this race was around Mile 12, when I heard the distant roar of the Wellesley students. I knew they were coming around Mile 13, but I was still surprised when I heard that roar. We must have been half a mile from them — I could see well down the road, but no visual sign of them — but even in that terrible weather, they came out in enough force to project that roar down the road. (I can’t resist repeating the word “roar,” perfect typo keyboard neighbour of “road,” so often in this paragraph.) I turned to a guy next to me, smiled, and said “Wellesley!” But he was suffering so badly that he didn’t even look at me. Once we got to Wellesley College I couldn’t help but waste some time and energy by going to the right side of the road and giving as many high fives and possible. It was the highlight of the race.

My in-race fueling strategy for Boston was the same as for LA. Since there were so many Gatorade stations (25 altogether, one every mile starting at Mile 2), I’d just drink Gatorade. But because I hit the wall a bit in LA, thought I’d try to sneak in a gel if I felt like my stomach could handle it. That’s what I did around Mile 12. I never hit the wall at all in Boston, so maybe it worked. (One advantage of running in heavy rain, by the way, is that your clothes don’t get covered in the sticky goo of spilled Gatorade. It just washes right off.)

After Wellesley, I knew the race trajectory. At Mile 15, you go downhill. From 16-21, you go up four hills of varying length and steepness. Then the last 5 miles are all downhill. Since the racing up to that point had been a little monotonous, I was eager for the Newton Hills when they came. Separating myself from my drafting partners, I sped off on the Mile 15 downhill, passing a whole bunch of people. Then, on the first of the Newton Hills, I took it pretty easy, and most of them caught back up. This pattern repeated on the three remaining hills: I pushed downhill and kept it very steady uphill. My pace up Heartbreak Hill was over 7:00/mile.

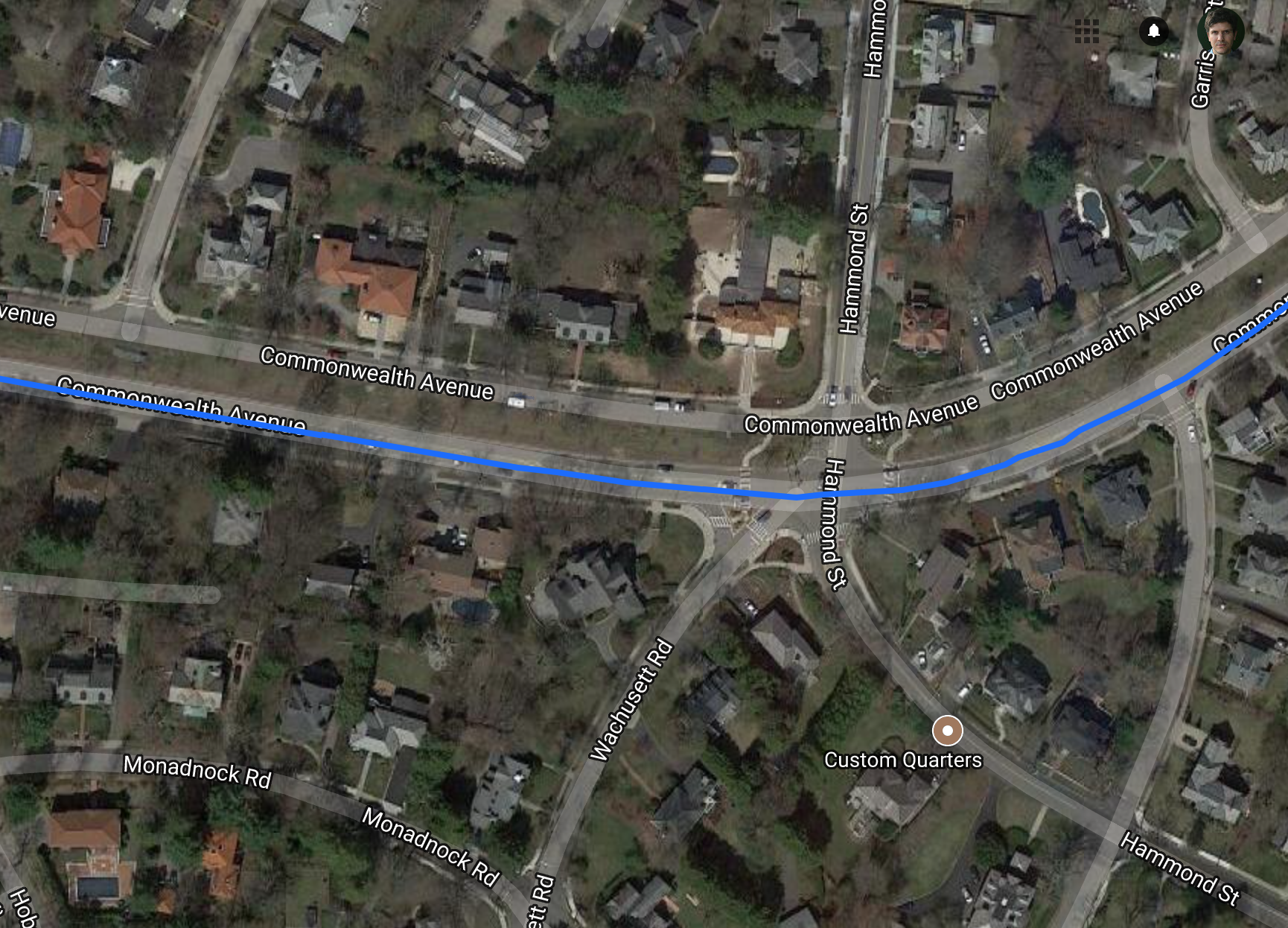

When I got to the top of Heartbreak Hill, I felt great. First, because I had made it there without destroying myself, still feeling like I had tons of energy for the downhill to the finish. The second reason was the name of the cross-street that marks the crest. The day before, on my way to the Goodwill, my path had taken me down Hammond St. in Lower Roxbury, and Marta had joked that it was a shame it wasn’t on the marathon course. But, amazingly, there is a Hammond St. on the marathon course — in probably the most crucial and important moment in the race. Coming to the top of Heartbreak Hill, I saw the sign for Hammond St. Clearly, Boston is my race.

I’ve read that those last 5 downhill miles can be the worst in the race, because cresting Heartbreak Hill gives you a false impression of being done (in fact, there’s at least half an hour of racing left) and because of the beating that downhill running gives tired quads. I was feeling good, and I enjoyed the end. Looking at my splits, I now see that I wasn’t going nearly as fast as I thought I was. I had the impression of absolutely flying through the last part of the course. I was passing people left and right — several hundreds of them, it felt like. But it’s not that I was speeding up, but that they were slowing down. My splits for the last miles in particular were pretty pathetic. But my whole strategy for the race was to pace myself by feel and compete not against my watch but against my fellow runners — so although I’m sure I could have pushed a little harder, I guess I was just sticking to my plan.

Photos of the finish line show me looking remarkably happy and all in one piece. That’s how I felt. Never before have I been sufficiently mentally composed at the end of a marathon to remember to stop my watch as I crossed the finish line. I did it here. (Touchingly, so did previously-unheralded second-place women’s finisher Sarah Sellers, who hasn’t learned to celebrate like a pro. She also used the same headband-over-hat technique as me!) I hadn’t been paying much attention to my time as I ran — my watch was set to lap pace, not overall pace, which turned out to be a great way of keeping me focused on “feel” — so as I looked down to to turn it off I was surprised to see how fast I’d run this brutal race. 2:52:40 is slower than I’d hoped to run Boston — but way faster than I thought I’d run it when I was sitting in that muddy tent in Hopkinton.

Post-race

As I crossed the finish line, however, I knew my race wasn’t over.

When I booked my plane ticket back in November, I’d stupidly assumed that, like most marathons, Boston started early in the morning, around 7 or 8am. I’d also thought the semester would still be in progress on April 16th, and — since I teach on Tuesdays — I’d need to head straight home. (Welcome back to Canada, where the semester ended for me this year on April 3rd!) I’d thus bought a return ticket for 3:50pm, thinking that would leave me plenty of time.

Once I realized my mistake, it was too late, and it would have cost more than the value of the ticket to change it. But I also thought this would add a fun extra challenge: run too slow, miss your plane. Of course, when the weather report came in, this became a more serious possibility, and a little less fun.

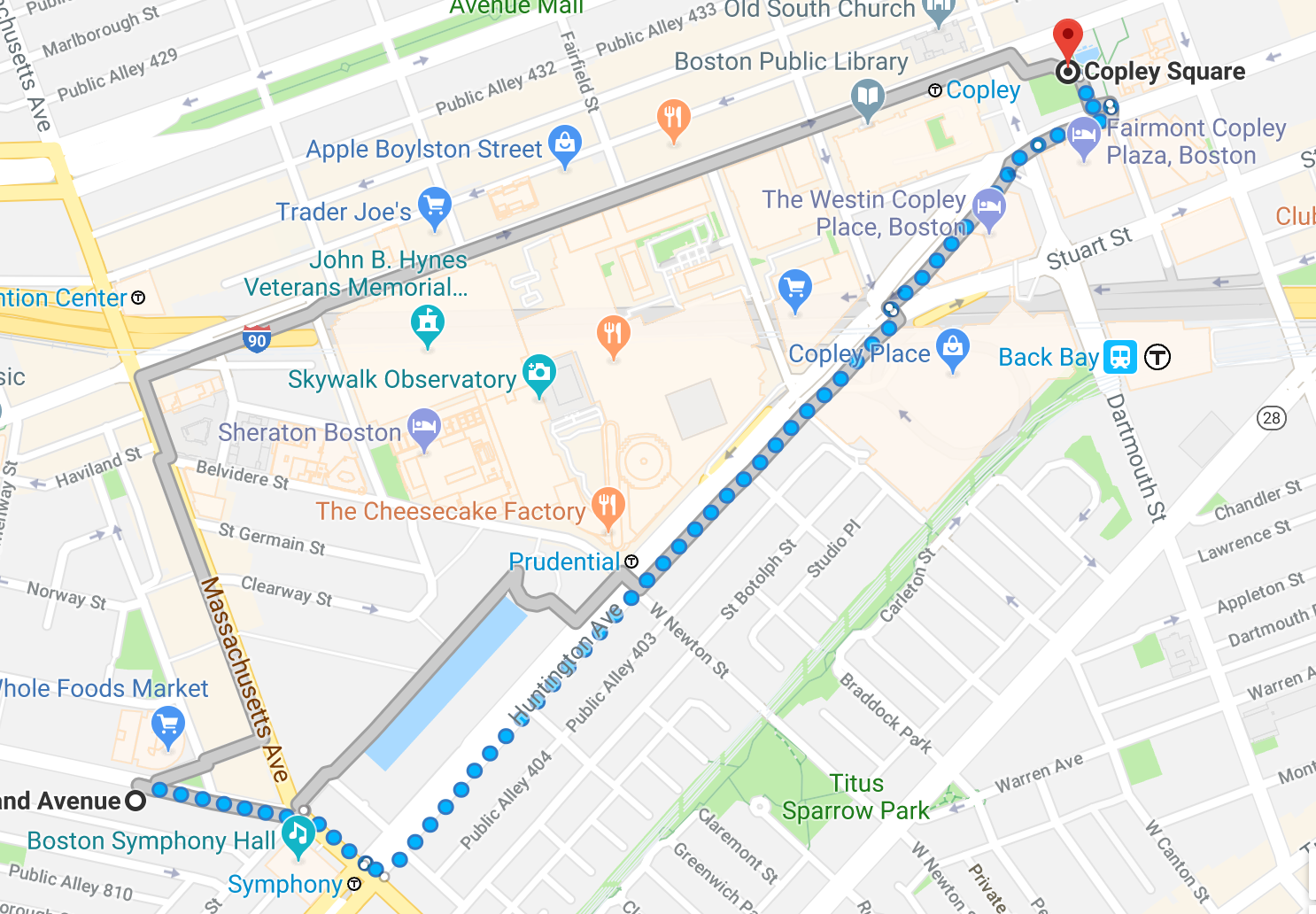

The weather also raised the problem of where to meet Marta after the race. Initially, the plan was for her to pack all our stuff, check out of the Airbnb, meet me at the finish, and get in the subway together right away. But waiting outside with all our stuff in pouring rain and gale force winds didn’t make sense. So the plan was for me to finish, grab my medal, and then drag myself one more mile, from Copley Place to our Airbnb on Westland Ave.

Knowing that I’d have to travel this extra mile — that I was really running 27.2 — really helped me stay on pace during the race. I kept thinking, “Don’t run too hard up this hill; if you collapse at the finish line, how are you going to make it back to the Airbnb, and what will Marta be thinking as she waits?” I actually became a little obsessed with this notion on the course — it kept going around in my head the way songs usually do when I run.

Anyway, it worked. I finished, grabbed my medal, put on the official Boston Marathon Heat Poncho (background for the photo at the top of this post), and got on my way. I didn’t stop for a single second and didn’t get anything to eat. I got a little turned around in all the post-race madness and ended up having to stop for directions at one point, but still made it back to the Airbnb by 1:05pm, so early that Marta wasn’t even downstairs waiting for me. When she finally showed up, she brought me the most delicious chocolate milk I’ve ever had, I got changed, and we caught an Uber to Logan. We were there by 1:40pm — ridiculously early for a flight that ended up being delayed almost two hours due to… the very same weather that had delayed 30,000 Boston marathon runners.

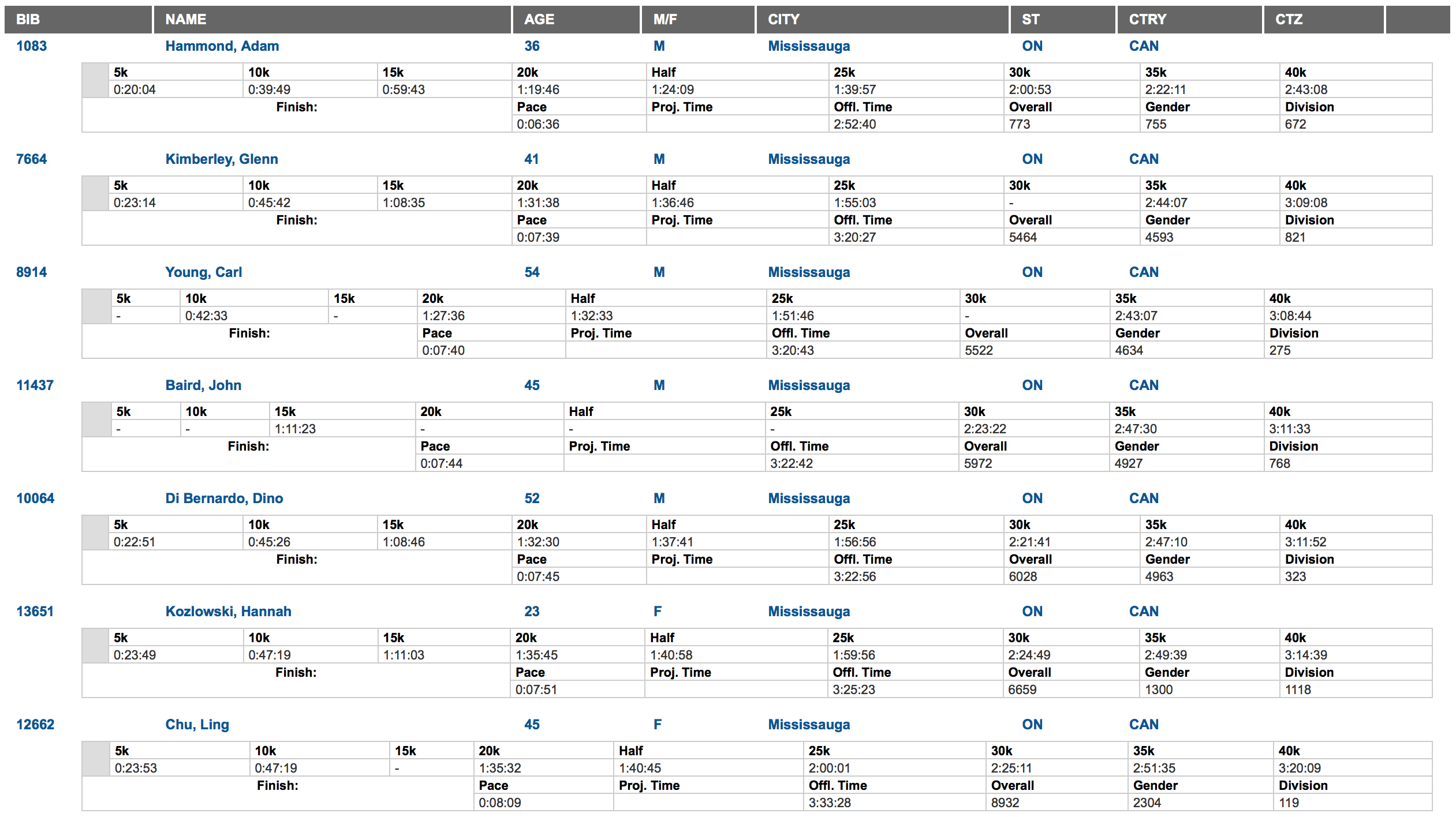

With lots of time to kill in the airport, I started reading the race reports. “Worst conditions ever.” “Slowest winning times in forty years.” “Over half the elites DNF.” Part of me was still a little disappointed with having run 5 minutes slower than my PR. And when I looked up my official time on the BAA website, I saw I’d come in 773rd — nowhere near the 28th place I’d ended up in at the similarly-sized LA Marathon. Sitting in the airport, reading those articles and tweets, helped me put it all into perspective. This was one of the hardest Boston Marathons ever. Boston is one of the most competitive amateur races in the world. I’d qualified 1,083rd with my Los Angeles PR of 2:47, and finished 773rd, suggesting this was the better performance. The winning times were over 10 minutes off what was expected, and I was only 5.

And I crossed the line smiling. And I made it back to the Airbnb in once piece. And we caught our plane.

All in all, as much as I enjoyed Victoria and Los Angeles, this was my best ever run.

Next

I told myself I’d take some time to re-evaluate marathon running after finishing Boston. Maybe it’s too hard on my body, maybe takes up too much time, maybe I’m not enjoying it anymore. But I enjoyed this Boston Marathon so much — this horrible, brutal Boston Marathon — that I obviously have to run another one. The fact that I finished so well with so much in the tank makes me think I’m capable of a time in the low 2:40s.

But the fact that I ran so well while staying so well within my abilities also makes me think maybe this is the way to approach it — not by trying to reach the absolute limits of performance at any cost, but trying to figure out how to balance speed with enjoyment. I pretty much nailed the balance here. (The key may be to save just enough energy to run an extra mile so that your partner doesn’t worry about you and you’re able to catch a plane. Can I claim that as The Hammond Strategy for Running Fast Yet Enjoyable Marathons©?)

The night before the marathon, for some reason, I started thinking about how you qualify for New York. I’d remembered that there was just a lottery, but on closer inspection I saw that there is also somewhat-tougher-than-Boston time-based qualification category. For 2018, the magic number for my age group was 2:55:00. I must admit I had that number in the back of my mind as I raced down Boylston St. If it holds for 2019 (it’s already too late to register for 2018), I’d make it, even with this climatically-challenged time. Maybe I’ll run another marathon between now and then, but for now, that seems like the next likely target.

Assorted final thoughts

At the time I registered for Boston, I had no permanent address in Toronto — I was renting week-to-week and looking for a place. As a result, my mailing address was Marta’s parents’ house in Mississauga. As a further result, my hometown for Boston is listed as Mississauga — which Marta finds horribly embarrassing, in a raised-in-the-suburbs kind of way. I see it as a great thing. If my hometown was listed as Toronto, I wouldn’t even be in top 10. Since it was listed as Mississauga, I’m my (imaginary) hometown’s #1 top finisher — by almost half an hour! (And Mississauga has a population of over 700,000, so…) For what it’s worth, I would also be the top finisher for Sudbury, Ontario (where I was born) and London, Ontario (where I grew up). If my hometown was Sudbury, Massachusetts, though, I’d be second; if it was London, England, I’d be sixth. I was in the top 50 Canadians. I was the second-placed person with the last name Hammond (fully six of us were greeted by their surname at the top of Heartbreak Hill).